Norwich Plastics of Cambridge, Ontario wants to lead North America in vinyl reprocessing. To this end, it diverts over 50 million pounds of the material from landfills each year. The company primarily deals with flexible and semi-rigid PVC scrap, plus smaller amounts of other thermoplastic waste. The company takes this material, breaks it down, and transforms it into pellets or powders, for reuse in a variety of customer products and applications.

“At the end of the day, we make feedstock. Customers call us up and say, ‘I need x million pounds of material, at this hardness, this tensile, this amount of flexibility and elongation,’” explains Director of Business Development, Tribu Persaud.

In addition to the Cambridge head office, the company has a facility in Woodstock, Ontario, and facilities in Orlinda, Cumberland City, and Erin, Tennessee. It has a North America-wide market reach and a very specialized focus. “We’ve been recycling vinyl almost exclusively since the early 1990s,” says Persaud, who notes that vinyl is simply the ‘street term’ for what is technically called polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Norwich Plastics offers closed-loop recycling solutions, also called circular recycling. In closed-loop recycling, products are used, recycled, and then transformed into repro to be used again by the brand owner/OEM or go into new products, thus keeping them out of landfills indefinitely. The closed-loop recycling process can be used for both post-industrial and post-consumer waste.

The company also facilitates toll processing. This is the term used when a producer recovers and recycles plastic scrap generated through its production process so that it can be reused. In such cases, Norwich Plastics consults with the producer and examines their scrap. The company “figures out what processing methods are relevant, then runs a trial for [the client]. We’ll determine their needs: do they need a powder, a pellet? What are the specifications they need the product to perform at? What properties do they need?”

The company also accepts scrap that is not designated for toll processing, careful in such cases to transform the scrap into something that will not compete with wares made by the material supplier.

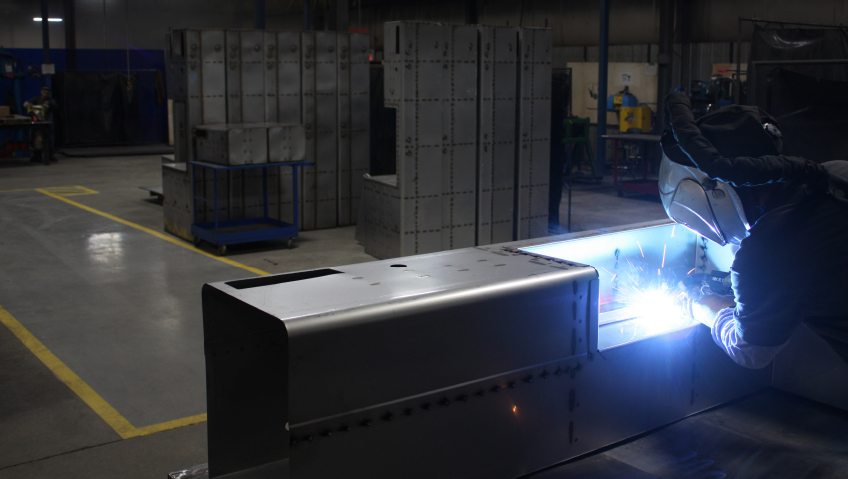

Reprocessing scrap can involve multiple steps, including reducing scrap to as little as 400 microns; compounding, in which reclaimed materials are custom-compounded into powders and pellets, according to client specifications; and contaminant removal/reduction, in which contaminants in reclaimable vinyl material are removed, reduced, or transformed into a vinyl composite, again depending on customer requirements.

Specific procedures include shredding, granulation, blending, air separation, and heating. The quantity of scrap, powder, pellets, and other finished goods handled by Norwich Plastics is staggering. “It’s a volume game. You have to do good volume to make money in this business,” notes Persaud.

Norwich Plastics has ISO 9001 certification and a very strict quality assurance regimen. “Everything has to be documented. You have to have written work instructions, written job descriptions. You have to have clear standards,” he says. “You have a third party come and audit your quality system.” He is strongly supportive of the ISO system, as “it makes the process accountable.” This makes particular sense as all the company’s work is self-performed. “We grind and process everything we sell. We don’t really use other people to do the work.”

Manufacturers use the reprocessed vinyl to make garden hoses, building products such as roofing membranes, and flooring and swimming pool components. Norwich Plastics also does “a small amount of injection moulded product applications,” says Persaud.

While the company has worked with hospitals for years, it wants to expand its reach in the medical market. In 2020, for example, it partnered with the Vinyl Institute of Canada—an industry trade group based in Niagara Falls, Ontario—and Environment and Climate Change Canada, a branch of the Canadian government, for a pilot program called PVC 123.

As the first program of its kind in Canada, PVC 123 aimed “to divert products from landfill and encourage the recycling of PVC medical devices in hospitals. Hospital operating rooms which produce the highest volume of intravenous bags, oxygen masks, and oxygen tubing waste, will be the first point of collection, after which, collected material will be manufactured into new products,” stated a Vinyl Institute press release.

Even after the official pilot ended, Norwich Plastics continued to work on this medical recycling initiative. “As of this year, we’ve converted it to a program where we’re charging the hospitals for the pickups. We basically funded that process for the last couple of years,” Persaud explains. Norwich Plastics currently has “about 20 facilities in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), from Woodstock, Ontario to Toronto, Ontario, participating in the program,” he says.

The company has big ambitions for this endeavour and is preparing to “take the program across the province. We’re speaking to facilities and looking to sign up facilities all the way from Windsor to Ottawa, and as far north as Barrie or Sault Ste. Marie,” he continues.

Norwich is also building its reputation within the U.S. medical recycling sector. The firm received a grant from the Vinyl Institute in Washington, D.C. to assist with a vinyl recycling project at in the Rochester Regional Health System in Rochester, New York.

This intense focus on vinyl recycling is a far cry from the early days of the company. Established in 1987 by Tribu’s father Paul Persaud and his business partners, Norwich Plastics initially handled “almost every polymer that was available to us that we could recycle and sell. We were seeing if we could make a go of the recycling business,” Persaud recalls.

In 1989, the company began to concentrate on PVC material, and by the early 1990s, Norwich Plastics was primarily a PVC recycler. Over the decades, branches were established in Woodstock and Tennessee. Persaud describes Tennessee as “a great state in terms of geographic location. You basically hit everything south of Ohio.”

His father remains involved in the business, while Tribu runs day-to-day operations. The firm is currently led by the family and business partner Glenn Longey, who looks after the Tennessee operations.

With a continent-wide reach, the company’s growth strategy is based on simple economics: “Does it make sense to pay the shipping [to a new region]? At the end of the day, we will go where it makes sense in terms of the business,” explains Persaud.

This system is highly dependent on the actions of the workforce and as such, he likes to hire “go-getters” and “self-doers,” who are loyal to the company and committed to its mission. “We’re looking for people that want to grow with the business. Most of the people [in] management started at entry-level jobs,” he adds. At present, Norwich Plastics has just under 50 employees in Canada and around half that in the United States.

While Norwich still relies on a paper-based production system, it is also forward-thinking and innovative. The company is “always looking at new methodologies” and new processes. For example, the company is heavily invested in developing composites made from two materials. “When we say composite, we’re taking PVC material and we’re mixing it with other materials,” says Persaud. “Other polymers are incorporated in there. You’re basically making a composite of PVC and whatever the other material is.”

Composite production “is something we’ve kind of been doing for a very long time, but now it’s really coming into play because of landfill diversion requirements and EPR legislation,” he points out.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is a strategy designed to make producers—rather than communities—more responsible for collecting and recycling. EPR and landfill diversion are two priorities for eco-friendly politicians seeking to encourage sustainability.

While a huge advocate for sustainable practices and recycling, Persaud finds the mounting regulatory requirements somewhat wearisome. The growing skilled labour shortage—as existing workers retire and not enough young people fill their positions—is another challenge. “Everyone is retiring. There was a time I could call 14 to 15 welders, and now there are three or four,” he states.

For all that, he is proud of Norwich Plastics’ impressive longevity and achievements. As for the future, Persaud is keeping a close eye on developments in the American market and elsewhere. “I think there’s a lot of toll manufacturing and toll recycling getting done up here in our Canadian operations but, in Tennessee, I think there’s going to be tremendous growth, especially as companies re-shore to the U.S.,” he states. “The other thing I would like to see moving forward is growth in the post-consumer side. To me, that’s where the market is going to go.”