Any given summer, in places like Mount Morris, Pennsylvania and Lakewood, Colorado, you can head just outside the city limits and see races that are part speed and part acrobatics as motocross racers hurtle and soar around a complex dirt course.

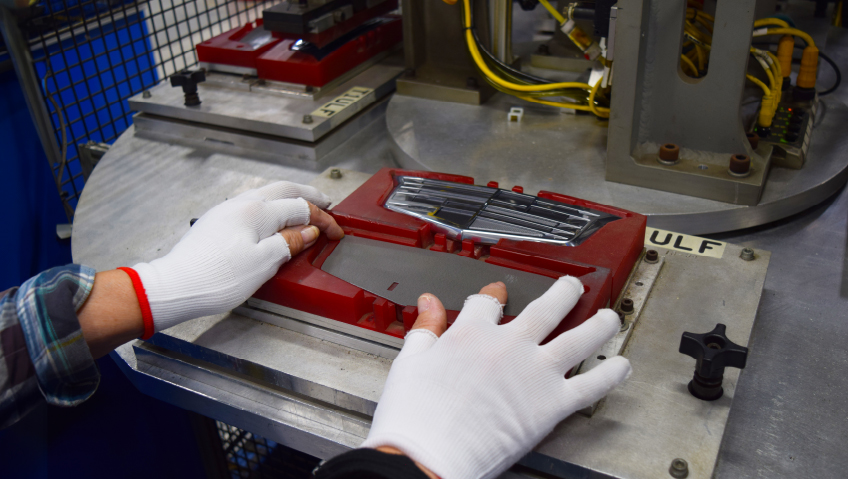

But don’t think these racers started out on those charged-up 500cc motocross machines. Almost all begin young on 50cc mini motocross bikes—small and fierce like their riders. And for many a present-day champion, the first ride was a yellow Cobra Motocross minibike. Little but mighty, these bikes were first built in 1993 in a tool and die shop in Ohio.

Cobra MOTO was first with race-worthy automatic motorcycles and had a monopoly on the market until global competitors got in on the game.

Putting the power into powersports

‘Powersports’ is the umbrella term for activities involving off-road vehicles like ATVs, snowmobiles, personal watercraft, and motorcycles. It’s also a market that was worth as much as $37 billion in 2022.

About 20 years ago, eyeing the powersport industry, an engineer named Sean Hilbert and business partner Phil McDowell put together a business plan that proposed transforming it with lighter, stronger, and faster engineering. The two partners bought Cobra in 2003 from the original owner and started work on higher-performance propulsion systems, building and expanding Cobra (now celebrating 30 years of building minibikes!).

Although for the first five or so years the new ownership focused on motocross, over time their transformation of the company has been sensational. They have evolved the business out of the original tool and die shop into a family of companies that manufactures roughly 2,000 propulsion systems used in everything from racing and firefighting to underwater vehicles and aerospace.

As part of their larger plan, Hilbert and McDowell also brought the Cobra Family of companies to Hillsdale, Michigan, where Cobra now runs all its operations. The Michigan Economic Development Corporation helped fund a move that would bring good manufacturing jobs to the state.

Making it in Michigan

“Michigan is a great place for manufacturing. I had a relationship with Michigan State University and the University of Michigan. I also knew, from a technology and a skill set standpoint, that this was a great place to manufacture,” says Hilbert, President of Cobra Aero.

“The skill sets around manufacturing and technology are second to none. There are more engineers per capita in Michigan than any place on the planet,” Hilbert says, and he should know, graduating from a joint MIT program with a degree in engineering as well as an MBA.

After Cobra’s move to Michigan, the company experienced the dizzy ups and downs that many businesses go through. “We grew like crazy for a couple of years and things were going well. Then the global economic meltdown happened,” says Hilbert.

Like many other industries during 2008 and over the next four years, Cobra’s powersport market shrunk by 80 percent. Three years later, the primary group of competitors in the market dropped from nine companies to two.

“We survived by very aggressively exporting and we were way ahead of the onshoring trend,” Hilbert says, modestly attributing the visionary strategy that put Cobra ahead of the curve to necessity. Looking at all the hard and soft costs of outsourcing, Hilbert and McDowell concluded that if the company was going to outsource to Asia, it had to cost 10 times less than what the product could be made for at home in the U.S.

As Hilbert saw it, “The easier calculation was that we could keep the men and women of Cobra working in Michigan, which not only was great for morale but also allowed us to very accurately fit what the market demand was.” This meant—for one thing—that Cobra did not have excess amounts of inventory lying around. “Our competitors were filing for bankruptcy because all their cash was used up in inventory while we were meeting the market demand as it came about,” says Hilbert.

The truth was that at the time, Cobra was still mainly committed to the production of mini dirt bikes which fell squarely into discretionary spending for most households, and that’s always the first spending to be cut when times get tough. And as with many manufacturers, the need to diversify suddenly became vital to the continued growth of Cobra.

Enter the military

With ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the demand for propulsion of small, specialized military vehicles was growing. Hilbert spoke to a U.S. Army general about this.

“He said, ‘So you’re an engine person? You have automotive experience and you know how to make performance engines?’ I said, ‘That’s what we do. Our background is automotive, but powersports is what we do now.’”

The army was using airplanes called ISRs, or ‘intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance’. Usually, when we think of reconnaissance, we think of something like fabulously fast, high-flying U2s. But small remote-control aircraft other than drones are also used as ISR airplanes. And these small planes are equipped with $250,000 camera systems to gather intelligence. The problem was that the engines in these planes were not much more sophisticated than a $300 hobby shop engine.

As the general told Hilbert, “I’m losing a million dollars of cameras every week because the engines aren’t performing.” So Cobra developed a solution, which resulted in contracts with the U.S. Navy and other militaries around the world.

Now, with aerospace customers on board, Cobra has also pursued new ventures made possible through electrification. “On the motorcycle side, we launched our first electric product this year. On the aerospace side, we have hybrid electric systems that are both electric and engine-powered. Those are two big transitions that the company’s going through and it’s happening as a result of digitizing our manufacturing processes.”

Powering into digital

Digital transition and Industry 4.0 are now very much at the core of Cobra’s manufacturing technology, with a particular emphasis on additive manufacturing and 3D printing. The business is rapidly transitioning from analog processes like injection molding and casting to creating products through additive manufacturing for both metals and plastics. Everything is printed versus being cast or molded, enhancing speed and creativity.

“In the aerospace business, we take additive manufacturing to the full end of the spectrum from product design to manufacturing,” Hilbert says. The many advantages include making prototypes a lot faster and providing the flexibility to completely rethink how a product is designed. The team is always thinking in terms of extreme lightweighting and consolidating the parts, and the efficiency gains have been game changers.

When the approach is applied to aerospace materials, costs are greatly reduced and as a result, Cobra does not feel the same cost pressure as in the consumer market.

Digitization has put Cobra in a position to stretch what it does for motorcycle manufacturing as well, says Hilbert. “Consolidation and extreme lightweighting features and forms allow function that you could never have with any other manufacturing technology.”

This commitment to 3D printing has led to impressive innovations. Cobra is making an engine cylinder for the U.S. Navy with improved cooling performance, for example.

“We want to be able to efficiently cool the engine under all kinds of circumstances, like in the hottest desert conditions. We have created these very small water passages that allow high coolant velocities inside the engine, and this cools an engine much quicker than any other way of doing it. But you could never cast that feature; you can’t machine that feature in because it’s internal to the engine itself.”

After taking a tool and die shop that specialized in minibikes and turning it into a multifaceted manufacturing company, the big question, of course, is what’s next?

“3D printing opened our eyes to a whole new range of ways to keep product lifecycle data. Suddenly it wasn’t just a material that you got from your supplier, but you can actually keep the entire manufacturing data as you’re creating this new part. You can look at temperatures, you can look at where they’re being built in the building chamber, oxygen content, and laser power.”

New vistas

Running the business today is also about managing more information for a fully traceable manufacturing system, all the way back to the very origins of a given part in Cobra’s catalog. Once again, Cobra is at the forefront of manufacturing. It’s creating databases that track the early origins of the part through additive manufacturing, subtractive manufacturing, assembly, and checkout. The team can even tailor efforts based on customer information. Big data has possibilities.

“Just imagine where that could go in the future,” says Hilbert. “We could mine those data sets using machine learning and get a full understanding of how our products are used in the marketplace and how we can make them better.”