First responders at a traffic accident at night not only have to act quickly to save lives, they also face the danger of oncoming cars while they do it.

That’s why shiny strips of 3M Scotchlite reflective materials are strategically placed on their uniforms to reflect back the oncoming headlights, alerting drivers and keeping the responders safe. These materials are a critical component of their protective gear.

Davey Textile Solutions, of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, has been working with reflective materials such as these for nearly 23 years, building a reputation for premium textiles in western Canada.

A future in fabrics

When the family started the business in 1986, before reflective materials were widespread, it was a true case of humble beginnings. “They bought a tiny fabric wholesaler, about 2,500 square feet of space, and it was full to the rafters with fabric,” says Dan King, Vice President of Davey Textile Solutions. “They were buying and sorting fabric and seeing if they could find new homes for it.”

Eventually, the business would move to its current 25,000-square-foot facility and acquire other textile companies in the 1990s, with plans for expansion. By the early 2000s, however, more work was moving offshore and the entire North American textile industry was in decline, as King explains. The company couldn’t survive as a whole business.

At a crossroads, the team began looking into reflective materials and saw a significant opportunity to stay relevant in a changing marketplace. “We realized we had to pivot the company. So we started looking around and landed on safety,” says King of the team’s strategy of identifying labour sectors with a need for high-performance gear.

Alberta is one of the largest oil and gas producers in the world, and working on those rigs requires robust safety equipment. Significant new safety legislation was also coming into play. In the past, dirty gear was a badge of honour for an experienced firefighter or oil drilling operator, for example, but there were now strict protocols about clean uniforms to prevent inhalation and absorption of toxins.

“We leaned on our awareness and our contacts through our prior 20 years of history,” King explains, “then we looked at how we could redesign reflective material to make it washable.”

This was the foundation for the striped garment that Davey Textile Solutions developed, along with its water-wash solutions for the reflective stripes. The plan was to partner with 3M Canada but, early on in the new venture, Davey was selling less than $100,000 in reflective products a year and needed to top that in sales before it could work with 3M.

The research route

Another challenge was durability. Commercial laundries were losing money on uniform cleaning because the striping was destroyed after one wash.

Davey Textile Solutions’ perseverance and innovation paid off, as the company increased sales and collaborated with 3M Canada to improve the quality of safety garments and address industry concerns.

“What’s unique about Davey is that we put resources into research and development, which is not common in the textile industry,” says Lelia Lawson, the company’s R&D Specialist.

A recent example of ingenuity is the development of an end-of-life sensor for safety garments. An initiative through the University of Alberta in Edmonton focused on firefighters and their protective equipment in particular. While these professionals are outfitted in personal equipment to be protected from the fumes in fires, they’re still exposed to carcinogens through the garments.

“Traditionally, these bunker gear garments would be laundered at most twice a year. But the carcinogens from the fires are in the fabric,” says Lawson. “Every time a firefighter would take off their gloves and touch their garment, all of a sudden that contamination would happen on their hand.”

As a result of these findings, Davey Textile Solutions and the University of Alberta are working on a sensor that degrades at the same rate as the outerwear fabric, while accommodating exposure to water and heat, to measure and indicate if the fabric is still protecting the firefighters from contamination.

The concept is not easy to put into production; the sensor is made with graphene, which is a conductor produced by laser technology, Lawson explains. “Essentially, you are burning the surface of a polymer to create this conductive tract that degrades at the same rate as the bunker gear.” From there, a multimeter is used to measure the wear, and when it reaches a certain level, it’s time to remove the garment from service.

Safety, but make it sustainable

Also on the company’s priority list is the development of new, sustainable fabrics—an important strategy in an industry that has the potential to produce a lot of waste. Davey Textile Solutions stands out as a leader in sustainability, with a key project aiming at acquiring cellulous fibre from hemp, a crop that requires less water and other inputs for its growth.

Since Canada legalized cannabis, industrial hemp has resurged as an agricultural crop, and it just so happens that hemp grows well in a northern climate like Alberta. The long stock of the hemp makes some of the best fibre, but because of cannabis prohibition, processing hemp had become a lost art. And, like many other industries post-COVID, textiles have also experienced some significant supply chain issues.

“The question was, ‘how can we create a sustainable textile hub in Alberta?’” says Lauren Degenstein, Davey Production Team Lead, who heads environmental initiatives.

The solution was using lyocell, a popular new fibre made from the hemp cellulose. “This is different from other regenerative cellulosic fibres like rayon where the processing is extremely toxic and damaging to the environment and human health, whereas the lyocell process is not.”

When lyocell breaks down, it doesn’t change from its original form; it coagulates and essentially reforms into a new fibre which is far more environmentally healthy, says Degenstein.

“It can also be used in the manufacturing of high-visibility striping and daily textile products for our trim,” she explains. “So we’re currently working with the University of Alberta, looking at growing conditions and the different ways to cultivate hemp.”

Beyond producing more environmentally friendly fibres, Davey is also a leader in efficiencies, eliminating the defects and scraps that are so often a part of textile manufacturing.

“We’re also looking at our carbon emissions. This is so new for many textile companies that there’s no information on how to monitor our devices or how we integrate different products. We’re in the exploratory stages of that,” Degenstein notes. That means trial and error in the process of finding more sustainable options.

“There can be pros and cons to trading a specific chemical in our finishing process. It could be damaging to one type of aquatic life but not another, so we want to make sure that solutions aren’t just a Band-Aid and they’re actually making a difference.”

Textile recycling, as well, is really just starting to take shape in the industry, so manufacturers are in a bit of a waiting game for the demand to catch up and make these initiatives more viable.

Future-forward

The team at Davey Textile Solutions, though, recognizes the challenges and sees that the future of the industry lies in investing in automation and sustainable methods and materials.

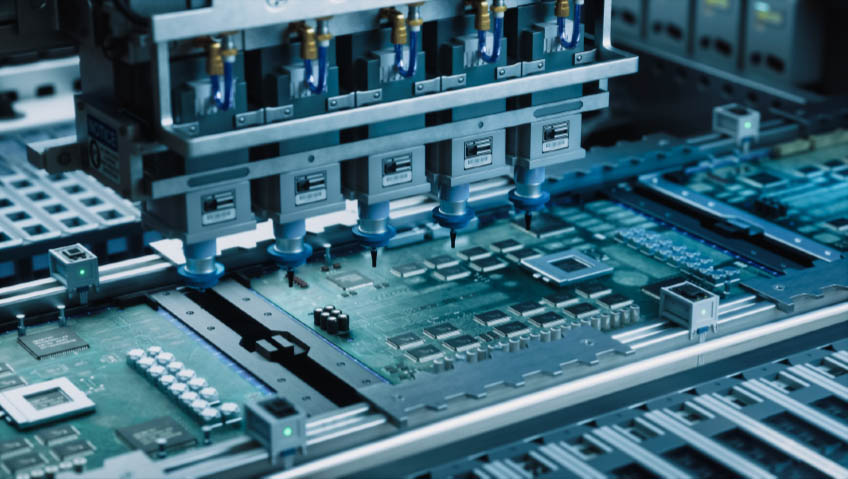

Discussing these plans for new technology and efficiencies, King explains that, “Right now in our weaving department we have one operator per laminator and we’re running at about 125 meters a minute through that facility. We want to get that up to 600 meters per minute with the same number of staff,” he says.

“Textiles used to be really innovative. The first computer was a Jacquard loom for weaving complex patterns, but the textile industry hasn’t advanced like other industries. We’re working to change that.”