Some companies are built from a business plan, while others are born from grit, opportunity, and a little bit of daring. For ProtoTier-1 Inc., a second-generation family-owned manufacturing company based in Ontario, the story began long before the company was incorporated in 1996. It started in Poland, with a mechanical engineer who dreamed of building something of his own in Canada.

When Paul Koziorowski talks about his father’s journey, it’s clear that ProtoTier’s roots run deep in both craftsmanship and entrepreneurial spirit. “My dad was a mechanical engineer in Poland,” he recalls. “He had a business there doing plastic injection molding, so he had that entrepreneurial kind of spirit about him. When we immigrated to Canada, he saw there was a market for prototypes and thought he could start something of his own.”

The early days weren’t easy. Paul’s father had to navigate a new language, a new business environment, and the challenges of establishing credibility in a competitive manufacturing landscape. What he brought with him, however, was a rare combination of technical expertise, business acumen, and the willingness to work hard and adapt. That foundation helped him quickly find his footing, first working for other manufacturers and then taking the leap into entrepreneurship.

After gaining valuable experience in the Canadian automotive industry, Paul’s father partnered with a trusted colleague to form what would eventually become ProtoTier-1 Inc. The company name itself reflects its niche: prototypes for Tier 1 suppliers, the key manufacturers who supply directly to automotive OEMs.

In the world of automotive manufacturing, Tier 1 suppliers are optimized for high-volume production. Their equipment, workforce, and supply chains are geared toward producing hundreds of thousands—sometimes millions—of identical components. But when it comes to producing prototypes or low-volume, short-run projects, those same large-scale operations can be inefficient or impractical. This is the gap that ProtoTier was designed to fill. Its sweet spot is runs of 3,000 to 5,000 pieces, a scale that is too small for many large manufacturers but perfectly aligned with ProtoTier’s capabilities.

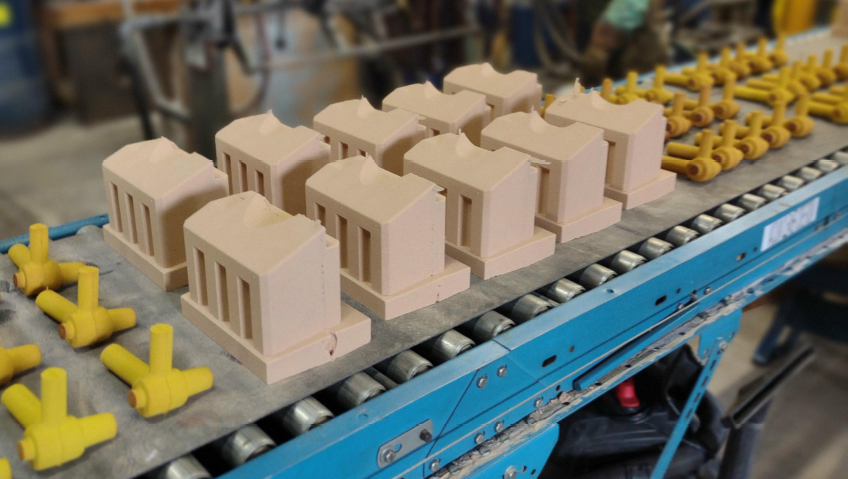

The company specializes in runs as small as a single prototype or as large as a few thousand components. The processes it uses mirror those of full-scale production facilities—stamping, forming, welding—but with a leaner, more agile approach that allows for rapid turnaround and cost effectiveness. “We manufacture in the same kind of ways as a production company would,” says Koziorowski, “however, we do it in a very cost-efficient way because we’ll do a lot of the parts trimming and holes on the laser as opposed to actual tooling, like you’d see in a production facility.”

This approach is particularly valuable in the prototype phase, when designs are still being refined. Instead of investing heavily in permanent tooling that might have to be scrapped if the design changes, ProtoTier uses flexible methods that allow for quick adjustments.

ProtoTier’s bread and butter is stamping and forming sheet metal, often for complex parts with multiple bends, curves, and cutouts. The team’s expertise lies in internal automotive components: hinges, latches, dash assemblies, brackets, and structural braces. These are not cosmetic parts, but critical elements that contribute to a vehicle’s safety, function, and durability.

A typical project begins when a customer provides a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) file. From there, ProtoTier unfolds the design into a flat pattern, determines the most efficient way to cut it, and programs its laser cutting systems to produce precise blanks. Those blanks are then formed on hydraulic or mechanical presses, using custom tooling created in-house on CNC machines. Sometimes the formed parts are finished on a 5-axis laser cutter, which allows for intricate trimming and the creation of features that would be difficult or impossible with traditional stamping dies.

Because ProtoTier controls so much of the process internally, the team can maintain tight tolerances and ensure that each part meets exact specifications, whether it’s a one-off prototype for testing or a few thousand pieces for a limited production run. Indeed, one of ProtoTier’s defining advantages is its commitment to doing as much as possible under one roof. This not only speeds up production but also safeguards intellectual property, a critical concern in industries where design leaks can be costly.

“As much as humanly possible, we do in-house,” Koziorowski says. “There are certain processes we just can’t do, like coatings or anodizing, but all the manufacturing we can keep here, we do. It allows us to maintain quality, speed, and control.”

And the benefits go beyond security and lead time. By keeping all stages of manufacturing in close physical and operational proximity, engineers and machinists can collaborate in real time. If a part needs to be adjusted, they can make changes on the fly instead of waiting days or weeks for an outside supplier to respond. This agility is one of the reasons customers return again and again.

While ProtoTier’s mainstay is automotive prototypes, sister company CanadaDocks is an example of how necessity can spark innovation. The idea emerged during the economic downturn of 2007–2008, when automotive work slowed and the company faced tough decisions. One of the partners needed a dock for his cottage, and rather than purchasing one, the team decided to build it themselves. “There was no real intention at that time to grow the company or go into that field,” Koziorowski shares. “It was created out of the need to survive and keep employees employed as long as possible.”

That single dock evolved into a product line and eventually into a brand that has carved out a place in the modular aluminum dock market. CanadaDocks’ products are designed for easy assembly, durability, and resistance to the harsh conditions of Canadian lakes and rivers. And just as in the automotive sector, precision manufacturing is a key selling point. The same laser cutting and CNC machining capabilities used for auto parts are applied to create perfectly aligned dock sections and accessories.

The synergy between the two companies goes beyond shared equipment—skills in design, material selection, and manufacturing processes flow both ways. Innovations developed for automotive clients often inspire improvements in dock designs, and vice versa. The result is a rare level of cross-industry creativity that keeps both companies competitive.

Yet for all its technical capability, ProtoTier’s defining trait might be the way it treats its people. With fewer than 30 employees, many with tenures exceeding a decade, the workplace operates more like an extended family than a factory. “We’re a small shop, and everybody’s almost like an extended family,” Koziorowski says. “We treat everybody fairly and respectfully as you’re just not a number here. We spend more time at work than at home, so we try to make sure it’s a place people want to be.”

Flexibility is a core part of that culture. Employees can adjust their start times to accommodate family commitments, and time off for personal events is met with understanding rather than pushback. Monthly barbecues in the summer, an annual Christmas dinner, and at least one off-site team-building event each year reinforce the sense of community.

It’s an environment where Monday mornings don’t feel like a grind. “It’s surprising on a Monday how many people will still be smiling and joking around compared to other places,” Koziorowski notes. The lighthearted atmosphere doesn’t mean a lack of discipline; when deadlines loom, the team works together to deliver.

While automotive manufacturing remains the backbone of ProtoTier’s business, the company has steadily diversified, taking on projects for American manufacturers seeking to keep production in North America, as well as clients in industries where production volumes are too small for traditional manufacturing plants.

The push toward electric vehicles has also brought new opportunities, and ProtoTier has produced battery cooling trays and other specialized components for EV manufacturers. The company’s ability to adapt quickly to new designs makes it an attractive partner for companies in fast-changing industries. “With the push for electric vehicles, we’ve started to do some electric car parts,” Koziorowski tells us. “With our knowledge and tools in-house, we’re very flexible.”

Rather than chasing rapid expansion, ProtoTier focuses on sustainable growth. The company owns land that could be developed, especially for CanadaDocks, but its priority is building customer relationships and expanding capabilities. “We’re content with our size right now,” Koziorowski says. “The growth we’re looking for is in outside automotive markets, diversifying the portfolio.”

At its core, ProtoTier’s success comes down to a blend of technical excellence, adaptability, and a genuine commitment to people, both employees and clients. The company’s ISO 9001 certification formalizes its dedication to quality, but the real proof is in the loyalty of customers and the longevity of staff members.

From a father’s vision in Poland to a thriving second-generation enterprise in Canada, ProtoTier’s story is one of resilience, creativity, and the value of keeping things close to home. This company has shown that a small, highly skilled team can compete with industry giants, not by outspending them, but by outthinking them.

As Paul Koziorowski puts it, “We’re not trying to be a big corporation. We’re a small shop where everybody knows each other, and that’s how we like it.”