Manufacturing has become a very sophisticated process designed to take advantage of maximum efficiencies to be competitive. A strategy called Just-In-Time (JIT) is a management approach that is used to control the flow of inventory to and from a business in order to minimize inventory levels and improve the efficiency of the manufacturing process.

The strategy, in essence, is to arrange the orders of raw materials such that goods are delivered only when required for production. The theory of Just-In-Time inventory management comes from Japanese management philosophy, and was first adopted by Toyota manufacturing plants in the early 1970s.

Advantages and disadvantages of JIT

This strategy provides a number of advantages, ensuring that materials are available when needed while minimizing the amount of storage space required. The approach also helps in reducing waste and loss. Materials are not left in storage for long periods of time and so aren’t subject to spoilage, loss, or obsolescence. And of course, JIT helps to lower inventory costs.

Certainly, the strategy also comes with its disadvantages. JIT inventory systems mean that a company only keeps a minimum amount of inventory on hand until it gets to the next delivery date. If a restaurant uses this system, it may only have enough food to last an average of four days. If a main competitor unexpectedly goes out of business, the inventory on hand might not be sufficient to meet the increased demand of new customers. On the other hand, the restaurant could see a sudden drop in business and food could spoil before it is used.

Links in the chain

A supply chain will consist of a number of elements—or links in a chain. At one end of the chain is a producer, who makes a particular component for their customer. In order to fulfill the order, they must have the necessary materials to produce the component, the workforce to create the component, and the means to transport the finished component to the customer. Each source for each part required may have its own distinct supply chain.

In order for any supply chain to function effectively, all the elements must connect smoothly. Over the years, there have been issues that have disrupted the orderly operation of supply chains. Trade wars, earthquakes, plant closures due to fires or tsunamis, labour disputes, transportation interruptions and shortages of raw materials have all had negative impacts, at times, on otherwise effective supply chains.

Goods must be able to be moved along the supply chain, and they must be able to be unloaded from ships, trains or transport trucks and put into warehouses on the docks or terminal until they are moved to their next location. Because of various issues associated with COVID-19, there is currently a shortage of dock workers as well as truck drivers, and this can cause a backlog for goods awaiting the next phase of their journey.

Of course, plant closures due to worker shortages can also disrupt production. Lack of materials needed to produce the product due to unavailability of a means of transport—truckers, shipping containers, or vessels—will mean that even if plants aren’t closed and have an available workforce, nothing can be achieved at desired levels if materials can’t be moved to where they need to be.

CBC News, in an October 2021 article, describes how “the COVID-19 pandemic waylaid the usual trends of supply and demand by wiping out both in early 2020 as factories shut down to keep workers safe, and consumers weren’t in the mood to buy anything but the essentials anyway.” Now that demand is on the rise again, suppliers are having a difficult time attempting to meet the increased demand for a wide range of items—from cars to appliances, iPhones and PlayStations.

The computer chip crisis

Supply chains for certain items have proven more precarious than others. Matthew Sparkes, in an article for NewScientist from March 2021, writes that, “The world is experiencing a computer chip shortage due to a perfect storm of problems including a global pandemic, a trade war, fires, drought and snowstorms. It has coincided with a period of soaring, unprecedented demand—in January alone, chip sales reached a record $40 billion.”

Computer chips, of course, are used in a wide range of electronic devices, perhaps even more than we may realize. Dishwashers, microwaves, refrigerators, mobile phones, medical equipment, watches, factory machinery, toys, laptop computers, and vehicles all take computer chips to function. In the wake of various disruptions in production, chips are not currently able to be produced fast enough to keep up with the demand.

As more workplaces moved to have employees work from home, and students of all ages began to study from home, new demands for technology increased. Home offices or home classrooms were being created and equipped. Office workers needed laptops, printers, scanners and webcams to work from home. Students also need digital technology to participate in online classes from home. And as people were required to follow ‘stay at home’ orders from health authorities, many also sought to beef up their home entertainment suites—in typical times, a welcome source of new sales for chip producers.

Originally, the shortage in computer chips was a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers in China and other locations were unable to work, so plants closed and production ceased, which resulted in supply issues. As items were produced, tighter restrictions at ports and international borders slowed their eventual movement to customers.

Impact on auto manufacturing

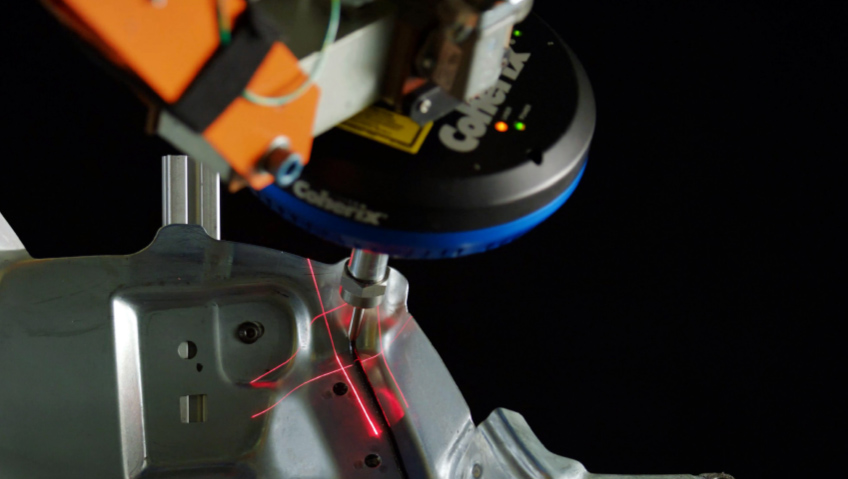

In the auto manufacturing sphere, companies will source parts from a breadth of suppliers; no auto manufacturer produces all the components needed for a vehicle in-house. In fact, an automobile is put together in what the industry calls an assembly plant. Engines, body components, batteries, tires, microchips and other parts must be delivered on time to the assembly plant.

“When the pandemic hit, the automobile industry girded for recession and cut back on orders to their suppliers, including chip manufacturers,” writes Bill Conerly in a July 2021 article for Forbes. “That would turn out to be a mistake, but for old-line car industry purchasing managers, it seemed pretty reasonable. When business picked up, their suppliers would ramp up production. The managers who were experienced ordering dashboards and bucket seats knew that their suppliers have nobody outside the auto industry to sell to, so they were always ready to restore production after a downturn.”

In May 2020, car sales returned and auto manufacturers began calling their suppliers looking to increase delivery of parts. For the most part, suppliers were able to step up and provide what was needed—except, that is, for computer chip suppliers.

As the pandemic had led to a great deal of remote work and online learning, chip companies pivoted to create chips for these devices since they were not producing them for the auto industry. When chip manufacturers were eventually asked to increase the supply of chips for the auto industry, they had to decline since they had committed to other customers—and the auto industry hit a rather large speed bump.

“The automotive industry has been hit particularly hard, illustrating perfectly the scale and complexity of modern supply chains,” writes John L Hopkins for GCN. “A car is made of about 30,000 components, sourced from thousands of suppliers around the world. If even one of these components isn’t available at the time of assembly, the system grinds to a halt and new cars can’t be shipped.”

The shortage of computer chips for the auto industry has led to some less than desirable solutions by manufacturers. “GM has sold some of its newest pickups and SUVs without advanced gas management systems or wireless charging features,” Hopkins shares. “Renault stopped installing the large screens that sit behind the wheel of its Arkana SUV models, while Nissan left navigation systems out of thousands of cars. Tesla even turned to rewriting its vehicles’ code so that the company could make use of the chips it did have at its disposal. But even that hasn’t completely spared Tesla from the shortage’s impact. The company was finding it particularly difficult to secure chips needed for its airbags and seatbelts, essential features for a car.”

The way forward

As we well know, the manufacturing industry is innovative and resilient. There is no doubt that lessons have been learned from the crises that have arisen during this pandemic. Methods and strategies that have worked in the past will need to be re-examined to explore ways to avoid such significant impacts. Hopefully, the result of this research will mean fewer disruptions in the complex and interconnected process that brings products to market.