“Work should be, for all of us, a word as honourable and appealing as patriotism.” – Dwight Eisenhower

Prior to the First World War, male factory workers dominated as factories were not considered a place for women to be. But this soon all changed when men picked up their arms to join the military during the Great War. The number of women in factories increased to meet the wartime production demands while men carried out their duties in battle. Women were needed, and they willingly chose to work.

The United States Government’s Department of Labor saw the need to create the Women in Industry Service (WIS) in 1918. The WIS coordinated with various organizations and corporations, and although the WIS was established to aid in a temporary situation, it eventually became a major fixture of the Department of Labor by 1920.

It then became known as the United States Women’s Bureau. “It was no coincidence that the Bureau was created the same year as the passing of the nineteenth amendment which gave women the right to vote. The First World War gave women new freedoms and opportunities and led to growth in the influence of women’s rights organizations,” says the Women in the Factories feature from the Elihu Burritt Library at the Central Connecticut State University.

During World War II, a global conflict of an unprecedented scale, women again took their places on production lines as many factories across North America were converted from producing normal household goods to military equipment to supply the needs of war.

Women across the country worked on assembly lines, out of a sense of patriotism or due to financial need with male breadwinners off at war. They ran drill presses, welded, used screw machines, produced munitions, and built ships and airplanes, among other activities. An estimated six million women began working in factories across the United States in positions that were previously unavailable. In fact, by 1944, women held one-third of manufacturing positions in the country. While some factories were producing military goods, most carried on with the same production of consumer goods as before the war.

When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt took a tour of the new workforce known as ‘production soldiers,’ she was impressed. But with so many women working on production lines, childcare centres became essential to enable them to work. She convinced her husband, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, to approve the United States Government’s first childcare facilities. Through the Community Facilities Act of 1942, seven centers were built to accommodate over 100,000 children. Industries across the nation were also encouraged to build childcare centres for workers.

Since the war, Rosie the Riveter has become a cultural icon with her bandana-tied hair, flexed arm, and her ‘We Can Do It’ slogan. At the time, however, the image was just one of many propaganda pieces intended to recruit women into the workforce. “If you’ve used an electric mixer in your kitchen, you can learn to run a drill press,” said an American War Manpower Campaign.

Canada had its own version of ‘Rosie the Riveter,’ geared at enticing women to fill positions in factories to contribute to the war effort, as men were fighting overseas. Indicating the essential need for women in factories while men were off to war, Canada’s Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, Liberal Party leader from 1919-1948, addressed the nation in August 1942. “Men and women are needed to make the machines, the munitions and weapons of war for our fighting men,” he stated.

Thousands of women answered the call. The peak of wartime employment during 1943-1944, saw approximately 373,000 women working in factories, according to Veterans Affairs in Canada Remembers: Women at War.

In September 1942, recruitment began with the Women’s Division of the National Selective Service in Canada. Initially, “Selective Service officers were to restrict employment permits to single women or to married women without children, as much as possible,” wrote Ruth Roach Pierson in Canadian Women and the Second World War.

Pierson also noted that “The September registration had revealed that in British Columbia, the Prairies, and the Maritimes, there were more than twenty thousand young single women without home responsibilities and willing to work full time.” Large production factories in Quebec and Ontario saw approximately 15,000 rural workers transferred to these facilities.

These women did their part to keep production facilities operating at peak capacity by learning the trades and skills necessary to support the ongoing war machine. The Canadian government also sponsored childcare centres so women could work.

Canadian women were vital contributors to Canada’s Victory Campaign whereby, in late 1944, Canadians liberated the southwestern region of the Netherlands, with which Canada had a special relationship, from the Germans. The strategic location was then utilized for logistical purposes.

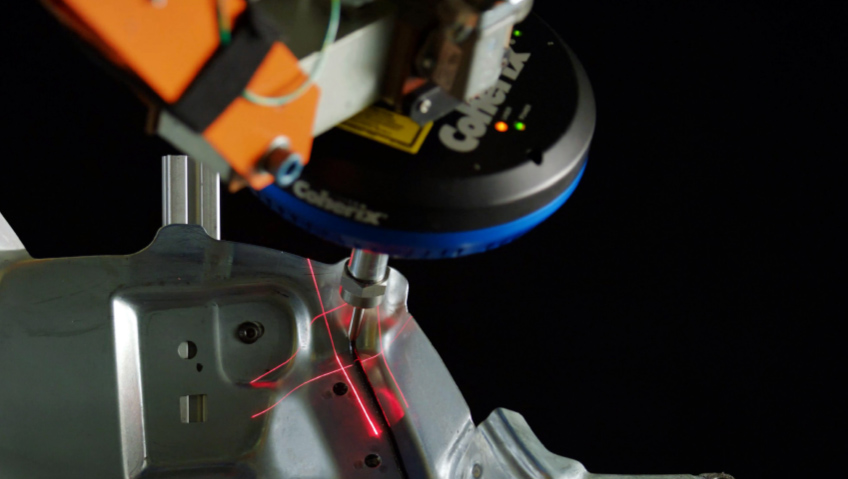

Women performed many repetitive tasks that required fine precision work in electronics, instrument assembly, and optics, for example, something that they proved to be very adept in doing. Women had proven that they could do ‘men’s’ work on factory production lines. These opportunities enabled women’s earning power, although for significantly less pay than their male counterparts. Although many women were already part of the workforce, the war effort was joined by those from middle and upper-class backgrounds who previously remained in the home.

After World War II, most women were let go from their jobs and returned home. The demand for war materials fell, and soldiers were returning home from the war seeking employment to get back on their feet and reacclimatize to civilian life.

Even so, between 61 and 85 percent of women wanted to remain in their jobs after the war. For them, working signified newfound freedom and independence. As Anne Montague, the founder of Thanks! Plain and Simple, an organization affiliated with the American Rosie Movement, noted in the Washington Post: “You know, they said about the men, ‘How ya gonna keep em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree?’ What I say about the women is, ‘How ya gonna keep ‘em knitting with yarn after they’ve seen Lockheed?’’’

In contrast, today, women are encouraged to pursue careers in the manufacturing industry, and technology and the quickly changing world of automation and augmentation will require specialized skills. More women are pursuing degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

According to the U.S. Department of Education, STEM degrees achieved by women increased almost sixty-seven percent during the 2008 to 2009 academic year. Close to thirty-three percent of STEM degree recipients in the U.S. were women from 2017 to 2018, equating to close to 240,000 degrees from colleges and universities. This number is up from the 2008 to 2009 statistic of over 143,000 degrees.

Women not only took positions across North America in the manufacturing sector in support of the war effort, but they also sacrificed their sons, husbands, fathers, and brothers. For that, women deserve our enduring gratitude.